Table of Content

- A standard for the Autonomous User Architecture

- A-User Control: The Autonomous Agent’s Brain

- Context Capture: The A-User’s First Glimpse of the World

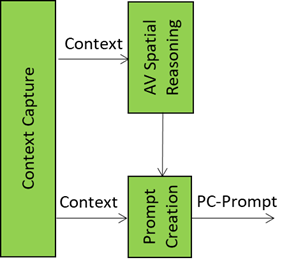

- Audio Spatial Reasoning: The Sound-Aware Interpreter

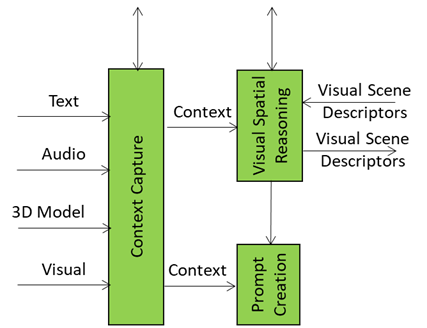

- Visual Spatial Reasoning: The Vision‑Aware Interpreter

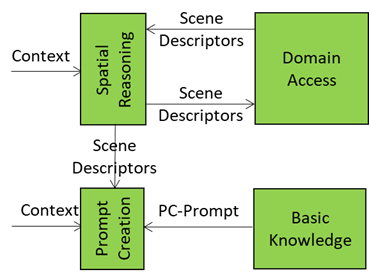

- Prompt Creation: Where Words Meet Context

- Domain Access: The Specialist Brain Plug-in for the Autonomous User

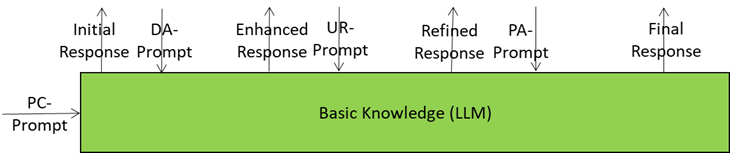

- Basic Knowledge: The Generalist Engine Getting Sharper with Every Prompt

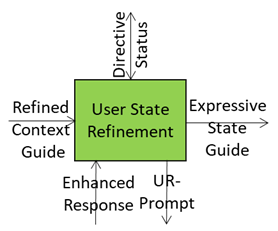

- User State Refinement: Turning a Snapshot into a Full Profile

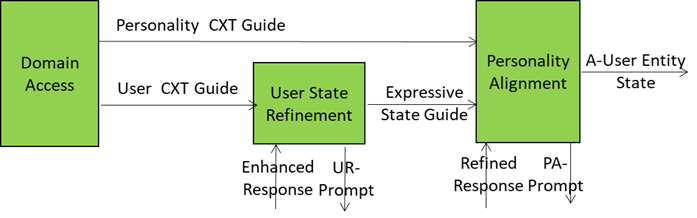

- Personality Alignment: The Style Engine of A-User

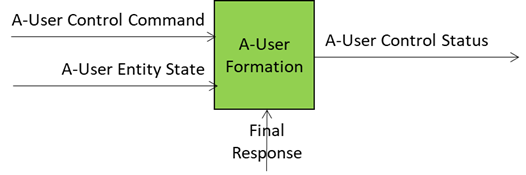

- A-User Formation: Building the A-User

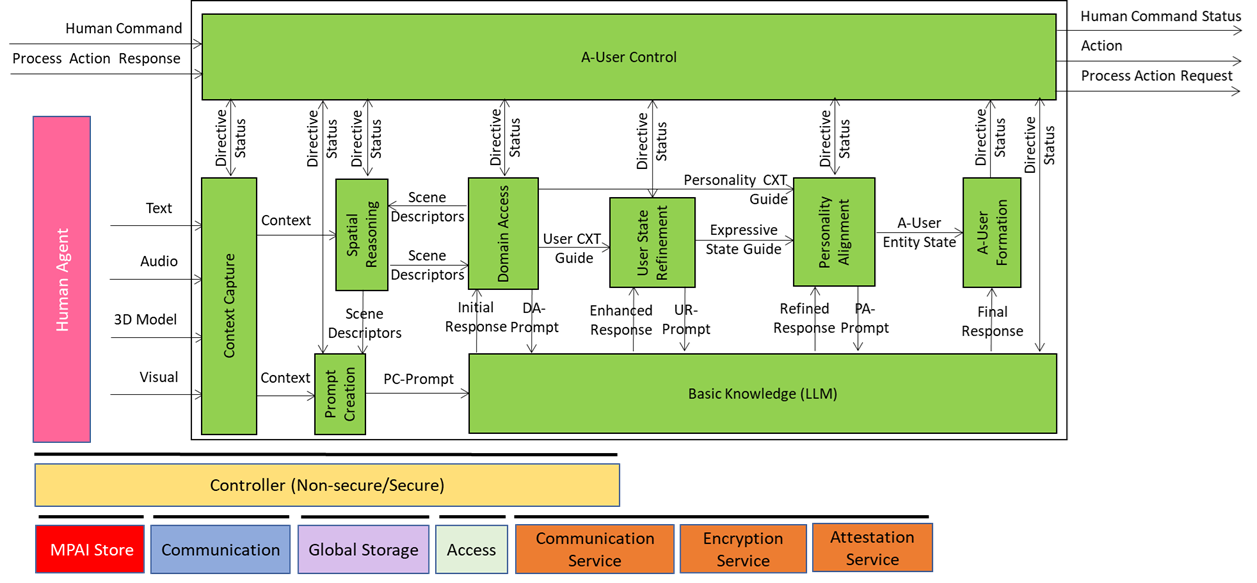

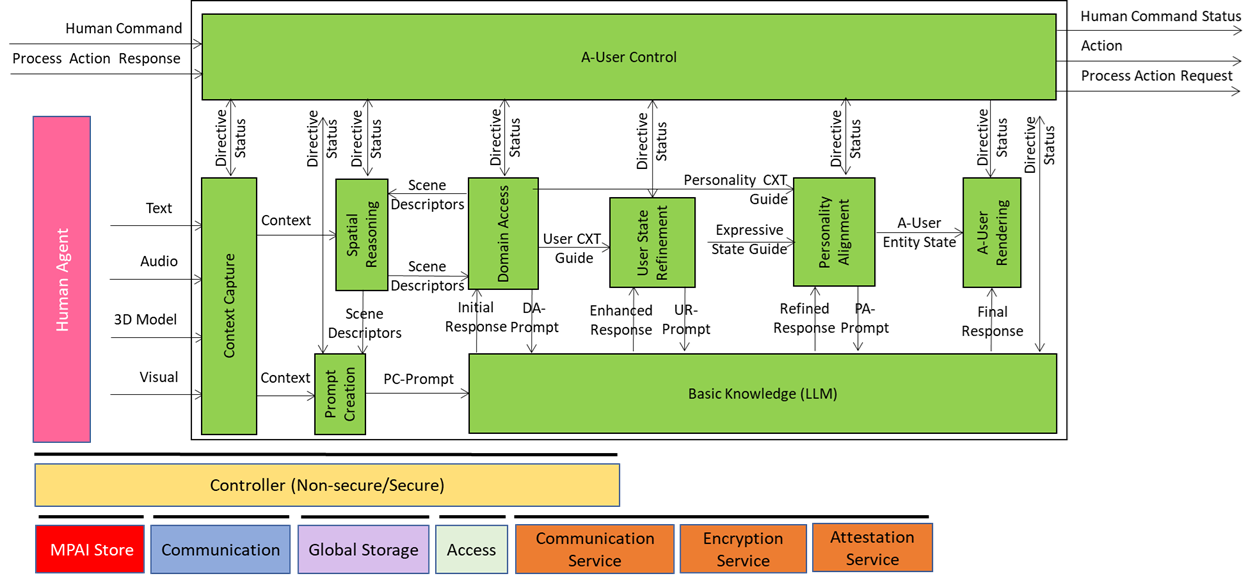

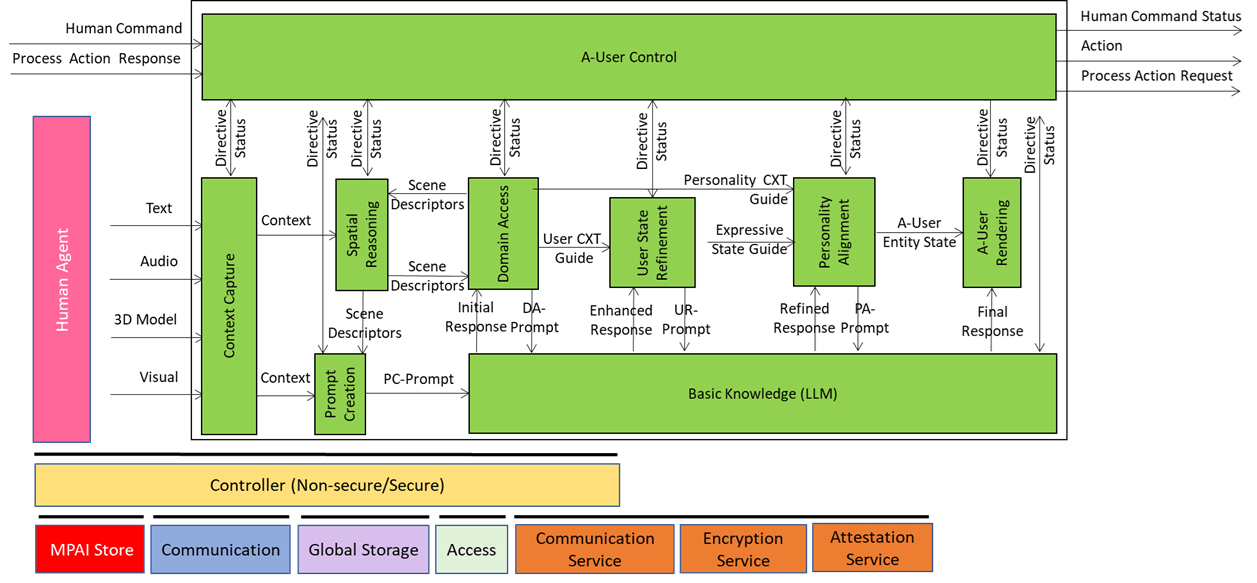

A standard for the Autonomous User Architecture

MPAI has developed 15 standards to facilitate componentisation of AI applications. One of them is MPAI Metaverse Model – Architecture (MMM-TEC) currently at Version 2.1. MMM-TEC assumes that a Metaverse Instance (M-Instance) is populated by Processes performing Actions on Items either directly or indirectly by requesting another Process to perform Actions on their behalf. The requested Process performs the Action if the requesting and requested Processes have the Rights to do. Process Action is the means for a Process to make requests.

A particularly important Process is the User. This may be driven directly by a human (in which case it is called H-User) or may operate autonomously (in which case it is called A-User) performing Actions and requesting Process Actions.

MMM-TEC provides the technical means for an H-User to act in an M-Instance. An A-User can use the same means to act but it currently does not provide the means to decide what (Process) Actions to perform. Such means are vitally important for an A-User to achieve autonomous agency and thus make M-Instances more attractive places for humans to visit and settle.

After long discussions, MPAI has initiated the Performing Goal in metaverse (MPAI-PGM) project. The first subproject is called Autonomous User Architecture (PGM-AUA). Currently, this includes the following documents: a Call for Technologies (per the MPAI process, a technical standard based on the responses received to a Call) accompanied by Use Cases and Functional Requirements (what the standard is expected to do), Framework Licence (guidelines for the use of Essential IPR of the Standard), and a recommended Template for Responses.

The complexity of the PGM-AUA project has prompted MPAI to develop a Tentative Technical Specification (TTS). This uses the style but is NOT an MPAI Technical Specification. It has been developed as a concrete example of the goal that MPAI intends to eventually achieve with the PGM-AUA project. Respondents to the Call are free to comment on, change, or extend TTS or to propose anything else relevant to the Call whether related or not to the TTS.

Let’s have a look at the Tentative Architecture of Autonomous User.

Anybody is entitled to respond to the Call. Responses shall be submitted to the MPAI Secretariat by 2026/01/21T23:59.

In the following, an extensive techno-conversational description of the TTS is developed.

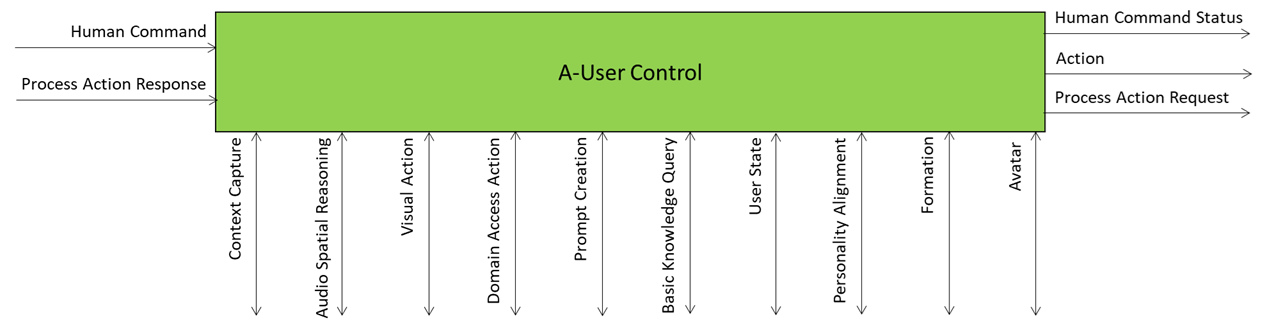

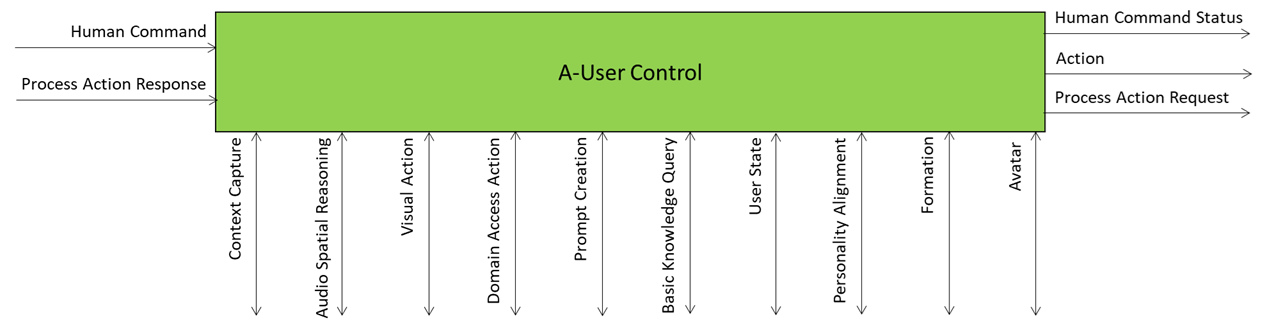

A-User Control: The Autonomous Agent’s Brain

A-User Control is the general commander of the A-User system making sure the Avatar behaves like a coherent digital entity aware of the rights it can exercise in an instance of the MPAI Metaverse Model – Architecture (MMM-TEC) standard. The command is actuated by various signals exchanged with the Ai-Modules (AIM) composing the Autonomous User.

At its core, A-User Control decides what the A-User should do, which AIM should do it, and how it should do it – all while respecting the Rights held by the A-User in and the Rules defined by the metaverse. Obviously, A-User Control either executes an Action directly or delegates another Process in the metaverse to carry it out.

A-User Control is not just about triggering actions. A-User Control also manages the operation of its AIMs, for instance A-User Formation, which can turn text produced by the Basic Knowledge (LLM) and the Entity Status selected by Personality Alignment into a speaking and gesturing Avatar. A-User Control sends shaping commands to A-User Formation, ensuring the Avatar’s behaviour aligns with metaverse-generated cues and contextual constraints.

A-User Control is not independent of human influence. The human, i.e., the A-User “owner”, can override, adjust, or steer its behaviour. This makes A-User Control a hybrid system: autonomous by design, but open to human modulation when needed.

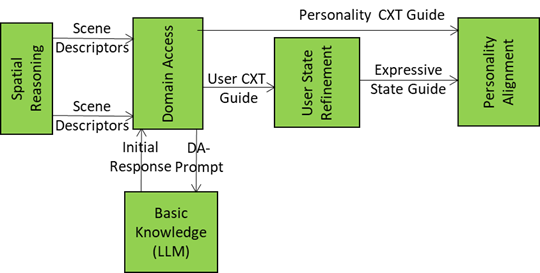

The control begins when A-User Control triggers Context Capture to perceive the current M-Location – the spatial zone of the metaverse where the User is active. That snapshot, called Context, includes spatial descriptors and a readout of the human’s cognitive and emotional posture called Entity State. From there, the two Spatial Reasoning components – Audio and Visual – use Context to analyse the scene and sending outputs to Domain Access and Prompt Creation, which enrich the User’s input and guide the A-User’s understanding.

As reasoning flows through Basic Knowledge, Domain Access, and User State Refinement, A-User Control ensures that every action, rendering, and modulation is aligned with the A-User’s operational logic.

In summary, the A-User Control is the executive function of the A-User: part orchestrator, part gatekeeper, part interpreter. It’s the reason the Avatar doesn’t just speak – it does so while being aware of the Context – both the spatial and User components – with purpose, permission, and precision.

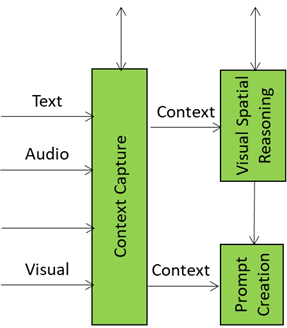

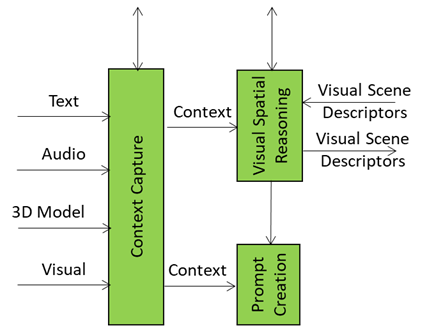

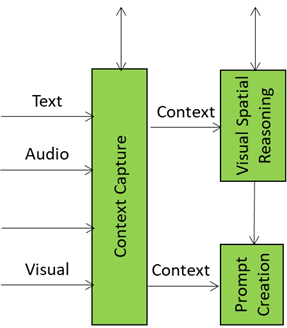

Context Capture: The A-User’s First Glimpse of the World

Context Capture is the A-User’s sensory front-end – the AIM that opens up perception by scanning the environment and assembling a structured snapshot of what’s out there in the moment. It is the first AI Module (AIM) in the loop providing the data and setting the stage for everything that follows.

When A-User Control decides it’s time to engage, it prompts Context Capture to focus on a specific M-Location – the zone where the User is active, rendering its Avatar.

The product of Context Capture is called Context – a time-stamped, multimodal snapshot that represents the A-User’s initial understanding of the scene. But this isn’t just raw data. Context is composed of two key ingredients: Audio-Visual Scene Descriptors and User State.

The Audio-Visual Scene Descriptors are like a spatial sketch of the environment. They describe what’s visible and audible: objects, surfaces, lighting, motion, sound sources, and spatial layout. They provide the A-User with a sense of “what’s here” and “where things are.” But they’re not perfect. These descriptors are often shallow – they capture geometry and presence but not meaning. A chair might be detected as a rectangular mesh with four legs, but Context Capture doesn’t know if it’s meant to be sat on, moved, or ignored.

That’s where Spatial Reasoning comes in. Spatial Reasoning is the AIM that takes this raw spatial sketch and starts asking the deeper questions:

- “Which object is the User referring to?”

- “Is that sound coming from a relevant source?”

- “Does this object afford interaction, or is it just background?”

It analyses the Context and produces an enhanced Scene Description containing a refined map of spatial relationships, referent resolutions, and interaction constraints and a set of cues that enrich the user’s input – highlighting which objects or sounds are relevant, how close they are, and how they might be used.

These outputs are sent downstream to Domain Access and Prompt Creation. The former refines the spatial understanding of the scene. The latter enriches the A-User’s query when it formulates the prompt to the Basic Knowledge (LLM).

Then there is Entity State – a snapshot of the User’s cognitive, emotional, and attentional posture. Is the User focused, distracted, curious, frustrated? Context Capture reads facial expressions, gaze direction, posture, and vocal tone to infer a baseline state. But again, it’s just a starting point. User behaviour may be nuanced, and initial readings can be incomplete, noisy or ambiguous. That’s why User State Refinement exists – to track changes over time, infer deeper intent, and guide the alignment of the A-User’s expressive behaviour done by Personality Alignment.

In short, Context Capture is the A-User’s first glimpse of the world – a fast, structured perception layer that’s good enough to get started, but not good enough to finish the job. It’s the launchpad for deeper reasoning, richer modulation, and more expressive interaction. Without it, the A-User would be blind. With it, the system becomes situationally aware, emotionally attuned, and ready to reason – but only if the rest of the AIMs do their part.

Audio Spatial Reasoning: The Sound-Aware Interpreter

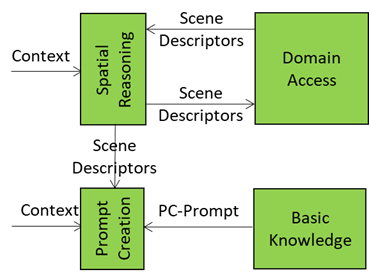

Audio Spatial Reasoning is the A-User’s acoustic intelligence module – the one that listens, localises, and interprets sound not just as data, but as data having a spatially anchored meaning. Therefore, Its role is not just about “hearing”, it is also about “understanding” where sound is coming from, how relevant it is, and what it implies in the context of the User’s intent in the environment.

When the A-User system receives a Context snapshot from Context Capture – including audio streams with a position and orientation and a description of the User’s emotional state (called Entity State) – Audio Spatial Reasoning start an analysis of directionality, proximity, and semantic importance of incoming sounds. The conclusion is something like “That voice is coming from the left, with a tone of urgence, and its orientation is directed at the A-User.”

All this is represented with an extension of the Audio Scene Descriptors describing:

- Which audio sources are relevant

- Where they are located in 3D space

- How close or far they are

- Whether they’re foreground (e.g., a question) or background (e.g., ambient chatter)

This guide is sent to Prompt Creation and Domain Access. Let’s see what happens with the former. The extended Audio Scene Descriptors are fused with the User’s spoken or written input and the current Entity State. The result is a PC-Prompt – a rich query enriched with text expressing the multimodal information collected so far. This is passed to Basic Knowledge for reasoning.

The Audio Scene Descriptors are further processed and integrated with domain-specific information. The response is called Audio Spatial Directive that includes domain-specific logic, scene priors, and task constraints. For example, if the scene is a medical simulation, Domain Access might tell Audio Spatial Reasoning that “only sounds from authorised personnel should be considered”. This feedback helps Audio Spatial Reasoning refine its interpretation – filtering out irrelevant sounds, boosting priority for critical ones, and aligning its spatial model with the current domain expectations.

Therefore, we can call Audio Spatial Reasoning as the A-User’s auditory guide. It knows where sounds are coming from, what they mean, and how they should influence the A-User’s behaviour. The A-User responds to a sound with spatial awareness, contextual sensitivity, and domain consistency.

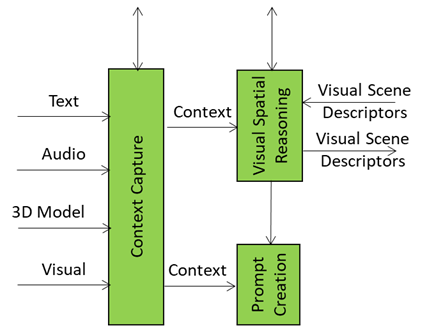

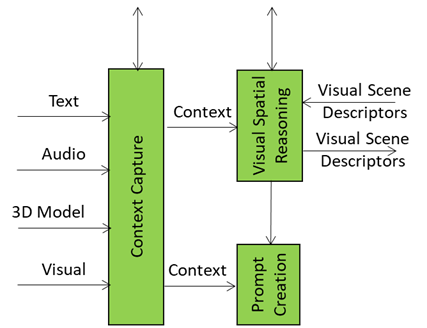

Visual Spatial Reasoning: The Vision‑Aware Interpreter

When the A-User acts in a metaverse space, sound doesn’t tell the whole story. The visual scene – objects, zones, gestures, occlusions – is the canvas where situational meaning unfolds. That’s where Visual Spatial Reasoning comes in: it’s the interpreter that makes sense of what the Autonomous User sees, not just what it hears. It can be considered as the visual analyst embedded in the Autonomous User’s “brain” that understands objects’ geometry, relationships, and salience.

Visual Spatial Reasoning doesn’t just list objects; it understands their geometry, relationships, and salience. A chair isn’t just “a chair” – it’s occupied, near a table, partially occluded, or the focus of attention. By enriching raw descriptors into structured semantics, Visual Spatial Reasoning transforms objects made of pixels into actionable targets.

This is what it does

- Scene Structuring: Takes and organises raw visual descriptors into coherent spatial maps.

- Semantic Enrichment: Adds meaning – classifying objects, inferring affordances, and ranking salience.

- Directed Alignment: Filters and prioritises based on the A-User Controller’s intent, ensuring relevance.

- Traceability: Every refinement step is auditable, to trace back why, “that object in the corner” became “the salient target for interaction.”

Without Visual Spatial Reasoning, the metaverse would be a flat stage of unprocessed visuals. With it, visual scenes become interpretable narratives. It’s the difference between “there are three objects in the room” and “the User is focused on the screen, while another entity gestures toward the door.”

Of course, Visual Spatial Reasoning does not replace vision. It bridges the gap between raw descriptors and effective interaction, ensuring that the A‑User can observe, interpret, and act with precision and intent.

If Audio Spatial Reasoning is the metaverse’s “sound‑aware interpreter,” then Visual Spatial Reasoning is its “sight‑aware analyst” that starts by seeing objects and eventually can understand their role, their relevance, and their story in the scene.

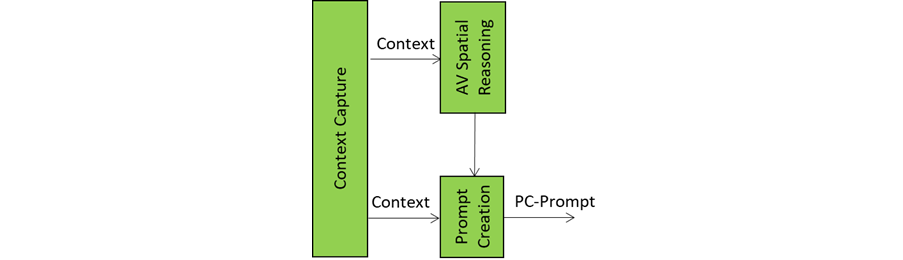

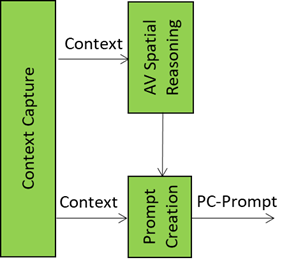

Prompt Creation: Where Words Meet Context

The Prompt Creation module is the storyteller and translator in the Autonomous User’s “brain”, It takes raw sensory input – audio and visual spatial data of Context (such as objects in a scene with their position, orientation and velocity) and the Entity State – and turns it into a well‑formed prompt that Basic Knowledge can actually understand and respond to.

The audio and visual components of Spatial Reasoning provide the information on things around the User such as “who’s in the room,” “what’s being said,” “what objects are present,” and “what’s the User doing”. Context Capture provides Entity State as a rich description of the A‑User’s understanding of the “internal state” of the User – which may a representation of a biologically real User, if it represents a human, or simulated when the User represents an agent. The task of Prompt Creation is to synthesise these sources of information into a PC‑Prompt Plan. This plan starts from what the User said, adds intent (e.g., “User wants help” or “User is asking a question”), includes the context around the User (e.g., “User is in a virtual kitchen”), and embeds User State (e.g., “User seems confused”).

This information – conveniently represented as a JSON object – is converted into natural language and passed to Basic Knowledge that produces a natural language response called the Initial Response – initial because there are more processing elements in the A‑User pipeline that will refine and improve the answer before it is rendered in the metaverse.

Prompt Creation gives the AI a sense of narrative, so the A-User can:

– Ask the right clarifying question.

– Respond with relevance to the situation.

– Adapt to the environment and User mood.

– Maintain continuity across interactions.

If the User says: “Can you help me cook?”

– Spatial Reasoning notes the User is in a virtual kitchen with utensils and ingredients.

– Entity State suggests the User looks uncertain.

– Prompt Creation combines these into: “User is asking for cooking help, is in a kitchen, seems unsure.”

This Initial Response is then passed to Domain Access, which may elaborate a new prompt enriched with domain-specific information (in this case “cooking”, when Basic Knowledge is not well informed about cooking).

Prompt Creation turns raw multimodal input and spatial information into meaningful prompts so the AI can think, speak, and act with purpose. It is the scriptwriter that ensures the A‑User’s dialogue is not only coherent but also contextually aware, emotionally attuned, and situationally precise.

Domain Access: The Specialist Brain Plug-in for the Autonomous User

The Basic Knowledge module is a generalist language model that “knows a bit of everything.” In contrast, Domain Access is the expert layer that enables the Autonomous User to tap into domain-specific intelligence for deeper understanding of user utterances and their context.

How Domain Access Works

- Receives Initial Response: Domain Access starts with the response of Basic Knowledge, the generalist model’s response to the prompt generated by Prompt Creation.

- Converts to DA-Input: As the natural language response is not the best way to process the response, it is converted into a JSON object called DA-Input for structured processing.

- Gets specilised knowledge by pulling in domain vocabulary such as, jargon and technical terms.

- Creates the next prompt by using this specialised knowledge:

- Injects rules and constraints (e.g., standards, legal compliance).

- Adds reasoning patterns (e.g., diagnostic flows, contractual logic).

All enrichment happens in the JSON domain and so is the produced DA-Prompt Plan – a domain-aware structure ready for conversion into natural language – called DA-Prompt – and resubmission into the knowledge/response pipeline.

Without Domain Access, the A-User is like a clever intern: knowledgeable but lacking depth and experience. With Domain Access, it becomes n experienced professional that can:

- Deliver accurate, context-aware answers.

- Avoid hallucinations by grounding responses in domain rules.

- Address different application domains by swapping or adding domain modules without rebuilding the entire A-User.

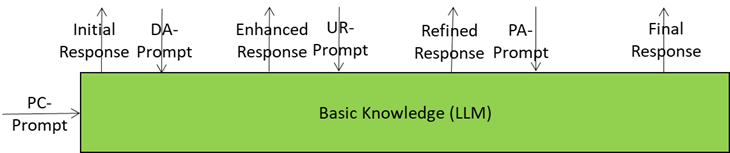

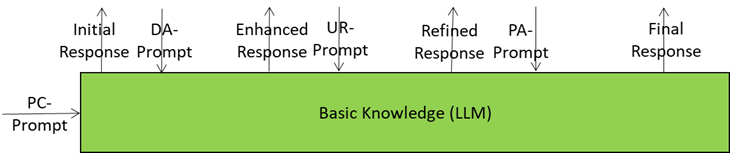

Basic Knowledge: The Generalist Engine Getting Sharper with Every Prompt

Basic Knowledge is the core language model of the Autonomous User – the “knows-a-bit-of-everything” brain. It’s the provider of the first response to a prompt but the Autonomous User doesn’t fire off just one answer but four of them in a progressive refinement loop, providing smarter and more context-aware responses with every refined prompt.

The Journey of a Prompt

- Starts Simple: The first prompt from Prompt Creation is a rough draft because the A-User has only a superficial knowledge of the Context and User intent.

- Domain Access adds expert seasoning: jargon, compliance rules, reasoning patterns. The prompt becomes richer and sharper.

- User State Refinement injects dynamic knowledge about the User – refined emotions, more focused goals, better spatial context – so the prompt feels more attuned to what the User feels and wants.

- Personality Alignment Tells A-User how to Behave: it ensures that the appropriate A-User’s style and mood drive the next prompt.

- Final Prompt Delivery: when Basic Knowledge receives the last prompt (from Personality Alignment) the final touches have been added.

This sequence of prompts eventually provides:

- Better responses: Each prompt reduces ambiguity.

- Domain grounding: Avoids hallucinations by embedding rules and expert logic.

- Personalisation: Adapts A-User’s tone and content to User State.

- Scalability: Works across domains without retraining.

Basic Knowledge starts as a generalist, but thanks to refined prompts, it ends up delivering expert-level, context-aware, and User-sensitive responses. It starts from a rough sketch and, by iterating with specialist information sources, it provides a final response that includes all the information extracted or produced in the workflow.

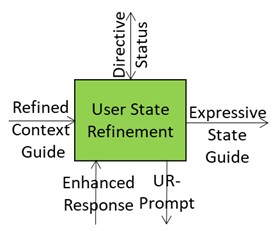

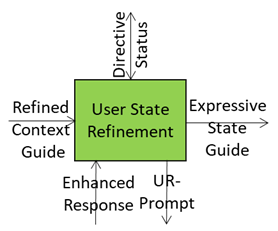

User State Refinement: Turning a Snapshot into a Full Profile

When the A-User begins interacting, it starts with a basic User State captured by Context Capture – location, activity, initial intent, and perhaps a few emotional hints. This initial state is useful, but it’s like a blurry photo: the A-User knows that somebody ps there, but not the details that matter for nuanced interaction.

As the session unfolds, the A-User learns much more thanks to Prompt Creation, Spatial Reasoning, and Domain Access. Suddenly, the A-User understands not just what the User said, but what it meant, the context it operates in, and the reasoning patterns relevant to the domain. This new knowledge is integrated with the initial state so that subsequent steps – especially Personality Alignment and Basic Knowledge – are based on an appropriate understanding of the User State.

Why Update the User State?

Personality Alignment is where the A-User adapts tone, style, and interaction strategy. If it only relies on the first guess of the User State, it risks taking an incongruent attitude – formal when casual is needed, directive when supportive is expected. If the User State can be updated the A-User knows more about:

- The environment incorporating jargon, compliance rules, and reasoning patterns.

- The internal state and can adjust responses to confusion, urgency, or confidence.

The Refinement Process

- Start with Context Snapshot: capture environment, speech, gestures, and basic emotional cues.

- Inject Domain Intelligence from Domain Access: technical vocabulary, rules, structured reasoning.

- Merge New Observations: emotional shifts, spatial changes, updated intent.

- Validate Consistency: ensure module coherence for reliable downstream use.

- Feed Forward: pass the refined state to Personality Alignment and sharper prompts to Basic Knowledge.

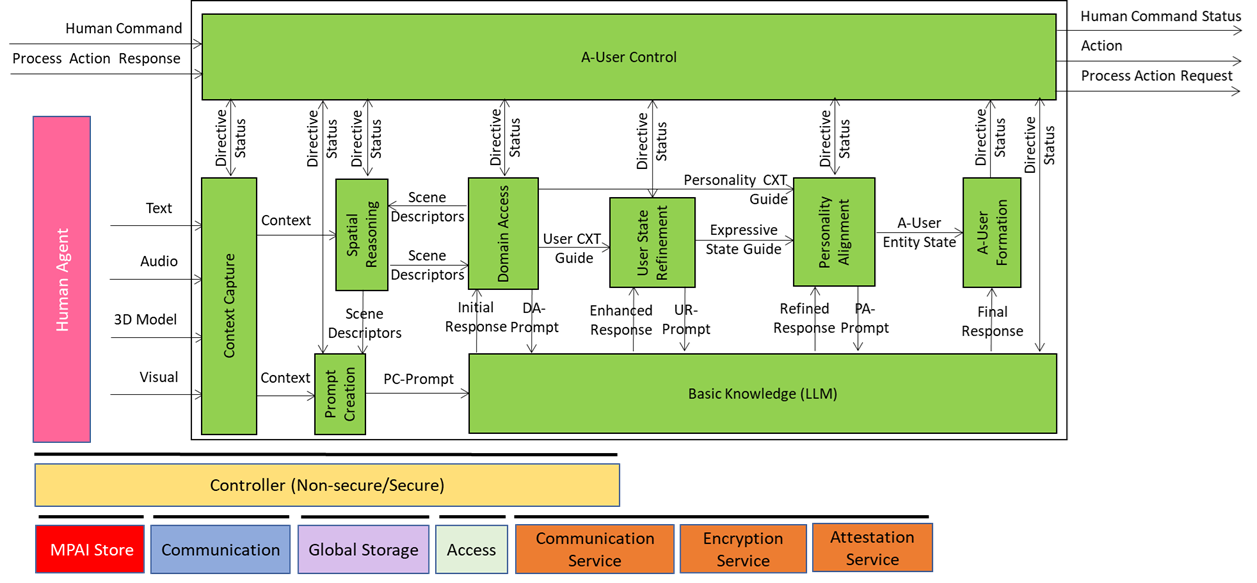

Personality Alignment: The Style Engine of A-User

Personality Alignment is where an A-User interacting with a User embedded in a metaverse environment stops being a generic bot and starts acting like a character with intent, tone, and flair. It’s not just a matter of what it utters – it’s about how those words land, how the avatar moves, and how the whole interaction feels.

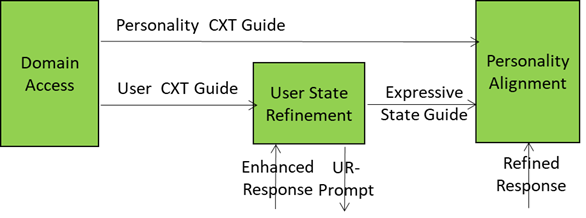

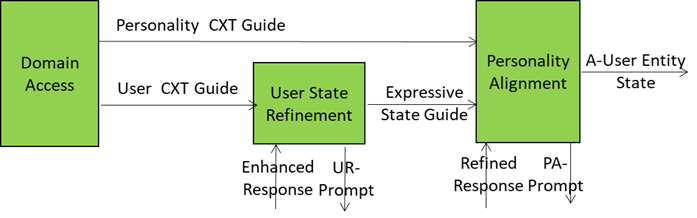

The figure is an extract from the A-User Architecture Reference model representing Domain Access generating two streams of data related to the User and its environment and two recipient AI Modules: User State Refinement and Personality Alignment.

This is possible because the A-User receives the right inputs driving the Alignment of the A-User Personality with the refined User’s Entity State:

- Personality Context Guide: Domain-specific hints from Domain Access (e.g., “medical setting → professional tone”).

- Expressive State Guide: Emotional and attentional posture of the User (e.g., stressed → calming personality).

- Refined Response: Text from Basic Knowledge in response to User State Refinement prompt.

- Personality Alignment Directive: Commands to tweak or override the personality profile (e.g., “switch to negotiator mode”) from the A-User Control AI Module (AIM).

A smart integration of these inputs enables the A-User to deliver the following outputs:

- A-User Entity State: the complete internal state of the A-User’s synthetic personality produced (tone, gestures, behavioural traits).

- PA-Prompt: New prompt formulation including the final A-User personality (so the words sound right).

- Personality Alignment Status: A structured report of personality and expressive alignment to the A-User Control AIM.

Here are some examples of personality profiles that Personality Alignment could use or blend:

- Mentor Mode: Calm tone, structured answers, moderate gestures, empathy cues.

- Entertainer Mode: Upbeat tone, humour, wide gestures, animated expressions.

- Negotiator Mode: Firm tone, controlled gestures, strategic phrasing.

- Assistant Mode: Neutral tone, minimal gestures, clarity-first responses.

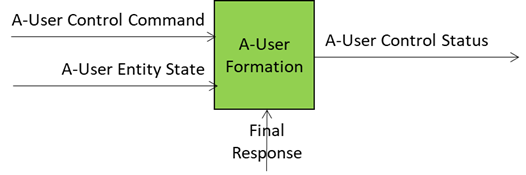

A-User Formation: Building the A-User

If Personality Alignment gives the A-User its style, A-User Formation AIM gives the A-User its body and its voice, the avatar and the speech for the A-User Control to embed in the metaverse. The A-User stops being an abstract brain controlling various types of processing and becomes a visible, interactive entity. It’s not just about projecting a face on a bot; it’s about creating a coherent representation that matches the personality, the context, and the expressive cues.

Here is how this is achieved.

Inputs Driving A-User Formation:

- A-User Entity Status: The personality blueprint from Personality Alignment (tone, gestures, behavioural traits).

- Final Response: personality-tuned content from Basic Knowledge – what the avatar will utter.

- A-User Control Command: Directives for rendering and positioning in the metaverse (e.g., MM-Add, MM-Move).

- Rendering Parameters: Synchronisation cues for speech, facial expressions, and gestures.

What comes out of the box is a multimodal representation of the A-User (Speaking Avatar) that talks, moves, and reacts in sync with the A-User’s intent – the best expression the A-User can give of itself in the circumstances.

What Makes A-User Formation Special?

It’s the last mile of the pipeline – the point where all upstream intelligence (context, reasoning, User’s Entity Status estimation, personality) becomes visible and interactive. A-User Formation ensures:

- Expressive Coherence: Speech, gestures, and facial cues match the chosen personality.

- Contextual Fit: Avatar appearance and behaviour align with domain norms (e.g., formal in a medical setting, casual in a social lounge).

- Technical Precision: Synchronisation across Personal Status modalities for natural and consistent interaction.

- Goal: Deliver a coherent, expressive, and context-aware representation that feels natural and engaging in response to how the User was perceived at the beginning and processed during the pipeline.