Abstract

In five years, MPAI – Moving Picture, Audio, and Data Coding by Artificial Intelligence, the international, unaffiliated, not-for-profit association developing standards for AI-based data coding – has been carrying out its mission, making its results widely known and its status recognised. However, not all are clear why MPAI was established, which are its distinctive features, and why it stands out among the organisations developing standards.

This is the first of a series of articles that will revisit the driving force that allowed MPAI to develop 15 standards in a variety of fields where AI can make the difference and have half a score under development. The articles will pave the way for the next five years of MPAI.

1 Standards have a divine nature

MPAI was established as a Swiss not-for-profit organisation on 30 September 2020 with the mission of developing data coding standards based on Artificial Intelligence. The first element that has driven MPAI into existence is the very word STANDARD. If you ask people “what is a standard?” you are likely to obtain a wide range of responses. The simplest, most effective, and although rather obscure answer is instead “a tool that connects minds”. A standard establishes a paradigm that allows a mind to interpret what another mind expresses in words or by other means of communication.

The example which is most immediate yet with a deep mening of standard is language itself. A language assigns labels – words – to physical and intellectual objects. Apparently, the language-defined labels are what make humans different from animals, even though there are innumerable forms of language used by animals that are less rich than the human one.

Words have a divine nature. So, it is no surprise that St. John’s Gospel starts with the sentence “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and God was the Word”.

Is this divine nature only applicable to language? Well, no. If we say that 20 mm of rain fell in 4 hours, we are using the language to convey information about rain that would be void of a quantitative value if there was not a standard for length called meter and a standard for time called hour.

Next to these lofty goals, standards have other practical purposes, A technical standard enacted by a country may be used as a tool to limit and sometimes even outlaw products not conforming to that standard, in that country. The existence of standards used for this purpose was the main driver toward the establishment of the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG): a single digital video standard that eventually uprooted scores of analogue television standards, with myriads of sub-standards. The intention was to nullify this malignant use of standards.

The goal of MPEG was to serve humans by enabling them to hear and see, thanks to machines that were able to “understand” the bits generated by other machines. In other words, it was necessary that machines be made able to understand the “words” of other machines.

Come 2020, Artificial Intelligence was not yet in the headlines, but the direction was clear. AI systems would be endowed with more and more “intelligence”, communicate between each other, and let humans communicate with them. What forms the “word” would take were not clear, but that the forms would be manifold was.

While MPEG had ushered in a new spirit in standardisation, it had also fostered a transformation in the way the need for standards would take shape and how standards would be exploited. In the early MPEG days, most industries still had research laboratories where the advancement of technology was monitored and fostered with a view of exploiting technology for new products and services. New findings would be patented and new patent-based products launched. The market would bless the winner among different products doing more or less the same thing with different technologies.

MPEG rendered useless the costly step of battling on patents in the market bringing to the standards committee a battle on standards. As a patent in a successful standard was highly remunerative, it did not take much time for the industry to invest in any patentable research. By industry, we intend “any” industry, actually not even industries that had a business in products and services. The idea was that a day would come that a patent would be needed in “a” standard. That single patent would repay the tens-hundreds-thousands of unused patents.

This was significant progress in terms of optimising efforts to generate innovation, and letting more actors join the fray. That progress, however, came at a cost, the disconnect of exploitation from generating innovation. An industry that had made an innovation to achieve an investment had every interest to see that innovation deployed. A company that has a portfolio of 10,000 patents may decide not to license a patent (in practice, by dragging its feet in releasing a patent) if that helps it license a more remunerative patent instead.

Certainly, this epochal evolution has resulted in a more efficient generation of innovation but is actually hindering exploitation of valuable innovations.

2 Inside MPAI

MPAI has been established to uphold the social value of standards, to adapt the notion of standard to the new Artificial Intelligence domain, and to rescue the right of society to exploit innovation. Let’s review how this has been implemented.

Laws pay much attention to standards because the patents that enable them give monopoly rights to exploit the patents to holders for a significant time span. This is the reason why a standards body requests that a proposal of a standard be accompanied by a declaration that, in simplified form, boils down to answering one of the three possibilities: if there are patent rights to the enabling technologies, does the submitter agree to allow the use of the patents for free, or are royalties applied, or is the use of patents not allowed? Setting aside the 1st and 3rd cases, in the second case the submitter is asked to declare that it will license the patents “to an unrestricted number of applicants on a worldwide, non-discriminatory basis and on reasonable terms and conditions to make, use and sell implementations of the above document” (i.e., the standard).

In past ages this used to be good enough, but is this still OK in an age when technology moves fast? Is it OK if it takes ten years for the declaration to be implemented and if, ten years later, a user discovers that the licensing terns are not acceptable?

A reasonable answer is that, no, this handling of patents in standards is not acceptable because society is deprived of technologies that may bring significant benefits to it. It may also not be acceptable to some patent holders because they are deprived of their ability to monetise the fruits of their efforts.

The MPAI handling of patents is exactly the opposite on this point. MPAI Members engaged in the development of a standard agree on a set of statements called “Framework Licence” that remove some uncertainty on the time and terms of the eventual licence.

Why only “some” and not all uncertainty? Because there are so-called antitrust laws that forbid this full clarification as this could be maliciously used to distort the market. As Monsieur de Montesquieu used to say: “Better is the enemy of good”, MPAI wants to make things that are good and not perfect things that create problems.

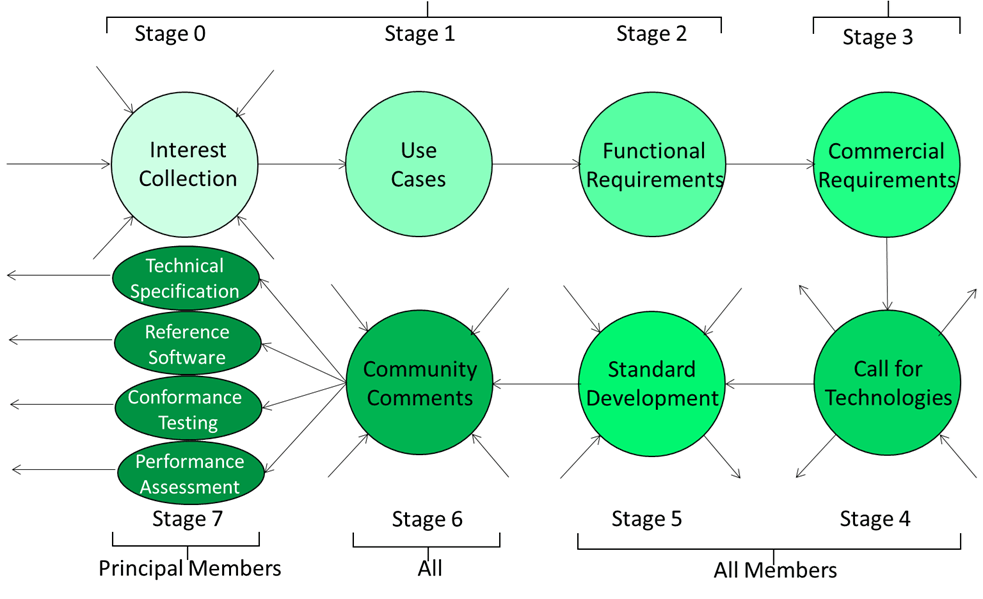

MPAI has developed a model process to develop standards which is based on a combination of openness – when the purpose of a standard is developed – and restriction – when the technologies making up the standard are developed. Figure 1 depicts the eight steps of a standard.

Figure 1 – The MPAI standard life cycle

Figure 1 – The MPAI standard life cycle

A standard may be proposed by anybody (Stage 0). To define the scope of the standard, use cases are developed (Stage 1). To define what the standard should exactly do, Functional Requirements are developed (Stage 2). Participation in these stages is open to anybody.

To define the conditions of use of the standard, Commercial Requirements are developed (Stage 3). Of course, MPAI is not engaged in any sort of commerce. “Commercial Requirements” are what above have been called Framework Licence. When the two types of requirements are ready, a Call for Technologies is issued (Stage 4).

Anybody can answer the call (Stage 5), but submitted technologies must satisfy the requirements. Proposed technologies are used to develop the exclusive standard with the participation of MPAI Members and the respondents to the call if they have joined MPAI. If they do not, their submission is discarded.

When the standard has reached a stability plateau, MPAI may publish the current draft before final publication (Stage 6). Anybody is entitled to send their comments to the MPAI Secretariat. Comments will be considered for inclusion in the published standard (Stage 7).

Stage 7 is divided in four Steps. The first Step concerns the publication of the standard, but a standard usually includes other Steps. Step #2 is the reference software, a conforming implementation of the standard that is included in the standard itself with reference to the MPAI Git from where the software – published with a BSD 3 Clause licence – can be downloaded. The third Step is Conformance Testing. An implementation of an AI Workflow conforms with MPAI-MMC if it accepts as input and produces as output Data and/or Data Objects (the combination of Data of a Data Type and its Qualifier) conforming with those specified by MPAI-MMC (see later for more about Qualifiers).

The last Step is Performance Assessment. Performance is a multidimensional entity because it can have various connotations, and the Performance Assessment Specification should provide methods to measure how well an AIW performs its function, using a metric that depends on the nature of the function, such as:

- Quality: the Performance of an AI System that Answers Questionscan measure how well it answers a question related to an image.

- Bias: Performance of the same AI System can measure the quality of responses depending on the type of images, i.e., the ability of the System to provide balanced unbiased answers.

- Legalcompliance: the Performance of an AIW can measure the compliance of the AI System to a regulation, e.g., the European AI Act.

- Ethicalcompliance: the Performance Assessment of an AI System can measure its compliance to a target ethical standard.

3 The MPAI mission

According to Article 3 of the MPAI Statutes, the mission of MPAI is to develop standards for data coding using Artificial Intelligence (AI). However, to fully understand this mission, two fundamental questions must be addressed: What exactly is a data coding standard? And what role does AI play in data coding?

In today’s digital society, it is widely recognized that we are inundated with data. One estimate predicts that by 2025, approximately 180 zettabytes (10²¹ bytes) of data will be generated – a 20% increase from the estimated 150 zettabytes produced in 2024. This raises critical questions: What does all this data represent? What are the costs associated with storing even a portion of it? And how expensive is it to transmit such vast amounts of information?

These concerns are not new. Since the advent of the digital era, it has been clear that applications often do not require all available data, or that data can be represented in more compact forms using fewer bits. This concept laid the foundation for data processing techniques that have been refined over time, ultimately enabling the widespread use of technologies like video.But new problems and needs surface. We continue to need less data with the same scope but there is a growing need to automatically “understand” the meaning of this many data and we are using ever larger amounts of data to transfer human knowledge to machines to equip them with new capabilities – what we have been accustomed Artificial Intelligence.

What does it mean to develop AI standards, then?

It is one thing to say that we need standards for AI and quite another to say what a standard for AI should specify. The first norm is that the standard should specify what flows though the interface of an AI System – data – but not what is in the AI System that processes input data and produces output data. What is an AI System is left undefined. It can be a large system, or a small one as long as the system retains a practical value as an individual entity.

A standard that enables the building of larger AI Systems from smaller components has advantages because it allows users to have a better idea of the operation of the system, it facilitates integration of components from disparate competence fields, enables optimisation of individual components, promotes the availability of components made available by competing developers, and more.

Component systems are thus a target for AI-based data coding standards, but what is the process that can produce candidate components for standardisation? The answer to this question is in identifying application domains and, within these, representative use cases. For each use case, an analysis is made of what components might be needed and which data enter and exit systems and components. The process could be implemented because the MPAI membership comes indeed from a variety of domains: media, finance, human-machine interaction, online gaming, entertainment, and more.

Having components – the building blocks – is a necessity but how should components interconnect with other components to make a system? And, once there is a system, how is it going to be executed?

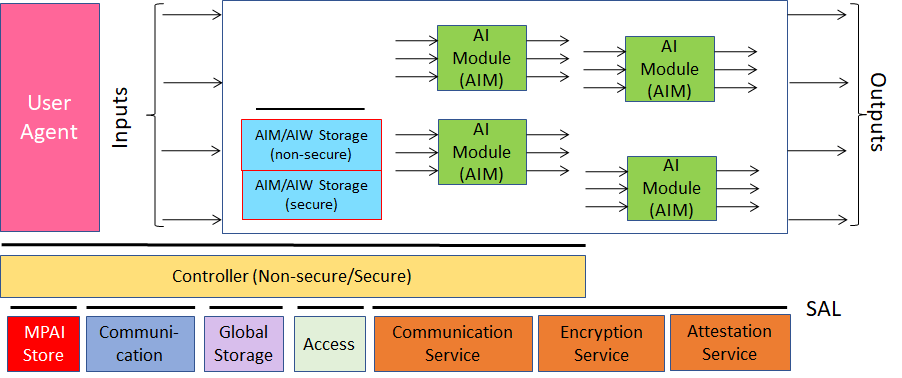

This was one of the first questions that MPAI had to address. The solution found was called AI Framework, an environment enabling initialisation, dynamic configuration, execution, and control of components called AI Modules (AIM) assembled in systems called AI Workflows (AIW).

The reference model of the standard – called AI Framework (MPAI-AIF), now at Version 2.1 – is depicted in Figure 2. The model assumes that there is:

- A User Agent so that users can act on the system.

- A Controller that

- Provides basic functionalities such as scheduling, communication between AIMs and other AIF Components such as AIM-specific and global storage.

- Acts as a resource manager, according to instructions given by the User through the User Agent.

- Exposes API for User Agent, AIMs, and Controller-to-Controller.

- Downloads AIWs and AIMs from the MPAI Store.

- Communication connecting an output Port of an AIM with an input Port of another AIM.

Figure 2 – Reference Model of MPAI-AIF

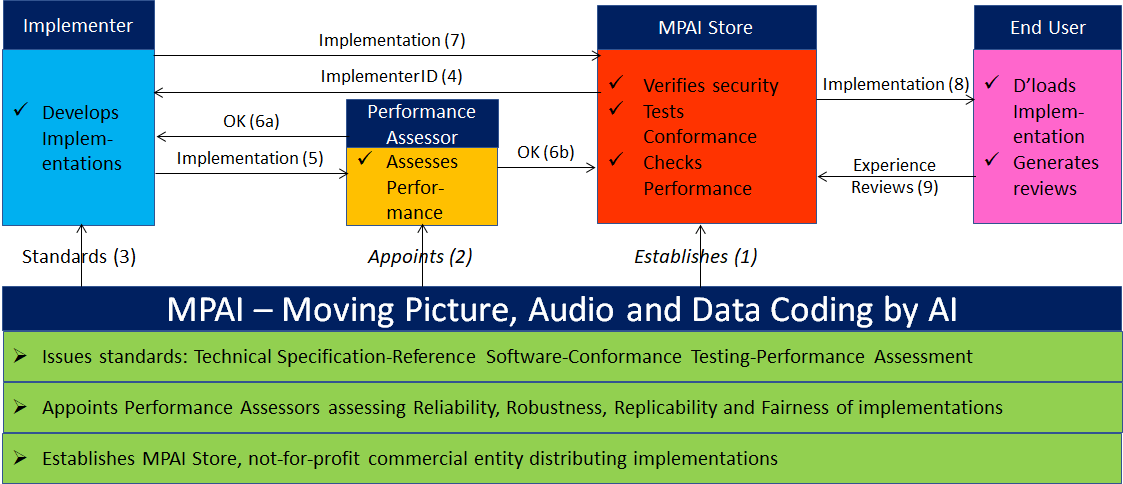

The MPAI Store is a foundational element of the AIF architecture. Assume that you are an AIM developer and that you want to make available your latest AIM for users to download and use in their systems, e.g., to replace an existing AIM with the same functionality in an app. Who certifies that the AIM is a correct implementation of an MPAI standard, and is also secure?

This is a new problem because, in the current context, the integration of components is done by a device, service, or application developer who has both the means and the technical expertise to do a proper job. Instead, MPAI is attempting to make possible a world where components – not full-fledged applications – can be downloaded by a user without particular expertise and integrated in an application developed by a third party.

This is an issue because any standard gives rise to an ecosystem whose actors are: the entity developing the standard, the implementer of the standard, the user of the standard, and the guarantor of the correct functioning of the ecosystem. Depending on the application domain, the guarantor can be the state, a certification authority, or even the manufacturer. Making the state the guarantor is not a solution for the current reality. In principle, the “manufacturer” of MPAI solutions (AIW) may very well not exist, but only the developer of basic components distributed as AIMs. So, we need a new entity – the MPAI Store.

The MPAI Store is incorporated in Scotland as a company limited by guarantee, a not-for-profit business set up to serve social, charitable, community-based or other non-commercial objectives. MPAI has signed an agreement with the MPAI Store giving it the exclusive rights to act as Implementer ID Registration Authority (IIDRA). Any entity wishing to develop and distribute AI Systems (AIW) and components (AIM) for use in an AI Framework (AIF) shall obtain an ID from the IIDRA.

How is an AIW or AIM implementation distributed? The registered implementer submits the implementation to the MPAI Store. The implementation is tested for conformance according to the Conformance Testing specification, a document developed, approved, and published by MPAI for each MPAI standard. If the implementation passes conformance testing, it is verified for security and posted on the MPAI Store website for users to access, download, and install.

All done, then? Well, in general at least, no. Conformance simply checks that an implementation receives data with the correct format, does what the reference standard specifies, and produces data with the correct format. But there is no guarantee that the AIM or AIW does a “good job”.

This is the consequence of the MPAI standard specifying input and output data and functionality but being silent of how the functionality is achieved. The Performance Assessment specification mentioned above makes up for the need of a measure of how “good” an implementation is. As we have already mentioned “good” has many dimensions and it would make no sense for the MPAI Store to attempt to issue statements on how good an implementation is. MPAI can appoint entities as Performance Assessors for specific domains and the MPAI Store can publish Performance Assessments of an implementation.

Figure 3 depicts the actors of the MPAI ecosystem and their functions.

Figure 3 – Management of the MPAI Ecosystem

Technical Report: Governance of the MPAI Ecosystem (MPAI-GME) V1.1 specifies the functions and responsibilities of the MPAI Ecosystem’s actors.

1 An overview of MPAI standards

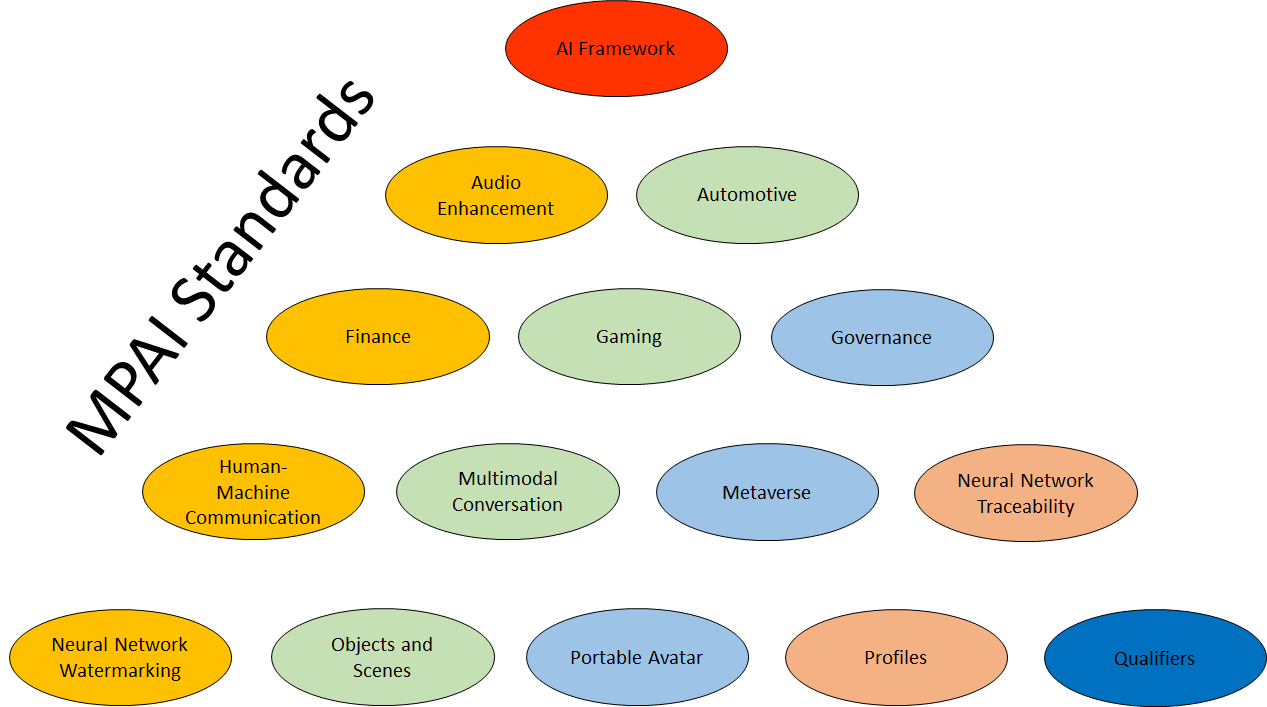

A foundational element of the MPAI initiative is that data produced in application domains benefits from appropriate representations, and that AI is an excellent technology that powers such representations. Of course, the semantics of the data often depends on the application, but the ways AI is applied are similar. AI is the current technology unifying disparate applications that share data generation.

Because of this, the scope of applications targeted by MPAI standards is most diversified. The current scope of applications is depicted by Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Application areas targeted by MPAI standards

Application domains in Figure 4 are organised in alphabetical order. So, the first is AI Framework of which some details have already been provided. Context-based Audio Enhancement (MPAI-CAE) is the next. In the first phase of this project four use cases were considered: Preservation of open-reel tapes, Emotion-enhanced speech, Speech Restoration System, and Enhanced audio conference. These are the names of the four AIWs specified in MPAI-CAE Use Cases (CAE-USC).

MPAI-CAE offers an opportunity to introduce the way MPAI identifies projects, standards and subdivisions, if any. An MPAI project is identified by three characters preceded by MPAI, e.g., MPAI-AIF for AI Framework and MPAI-CAE for Context-based Audio Enhancement. A project that is expected to originate a standard is identified with the same acronym of the project. A project may originate a single document for the corresponding standard. This is the case of MPAI-AIF. A standard may be revised. Different revisions are called versions. A version is indicated with the letter V followed by two digits separated by a period. For instance, the latest version of MPAI-AIF is V2.1.

Some areas are prolific of standards. In its first edition, MPAI-CAE first dealt with four Use Cases. Subsequently, another sub-project was started: Six degrees of freedom. Clearly, this belongs to the MPAI-CAE project but is definitely different from one collecting Use Cases. Adding the new standard to the existing Use Cases would make the standard unwieldy and possibly not attractive to implementers. For this reason, a new “part” of the MPAI-CAE standard was introduced: 6DF. Therefore, the MPAI-CAE standard has the current structure:

Standard: Context-based Audio Enhancement (MPAI-CAE)

Part 1: Use Cases (CAE-USC) V2.3

Part 2: Six degrees of Freedom (CAE-6DF).

Part 3: Audio Object Scene Rendering (CAE-AOR).

Part 2 and 3 have not been approved yet.

The Automotive project is called Connected Autonomous Vehicle (MPAI-CAV). Its goal is to specify a Connected Autonomous Vehicle’s Architecture composed of Subsystems – implemented as AI Workflows (AIW) – and Components – implemented as AI Modules (AIM) – exchanging Data Types specified by JSON Schemas. MPAI-CAV started as a single standard, then the need for an Architecture standard was identified (CAV-ARC) and finally a new part was developed, approved, and published: Technologies (CAV-TEC), currently at V1.0.

The Finance project has an even broader name: Compression and Understanding of Industrial Data (MPAI-CUI). A first version of the standard was published as MPAI-CUI, but the new V2.0 under development benefits from the clarification explained above and is called Company Performance Prediction (CUI-CPP). Its goal is to specify the AI Workflow, the AI Modules, and the Data Types enabling a system receiving Finance and Governance Data, Primary Risk Data, (i.e., data for which an authorised AI Module is available), Secondary Risk Assessment (i.e., data for which only company-provided assessment is available), and a Predictions Horizon to produce Governance Descriptors, Primary Default and Discontinuity Descriptors, and Secondary Discontinuity Probability.

The next area is Human-Machine interaction. This is not one but is two projects. Let’s start from the second (in alphabetical order) which was the first to be kicked off: Multimodal Conversation (MPAI-MMC). Currently at V2.3, MPAI-MMC provides technologies enabling a machine to interact with an Entity (a human but potentially a machine as well) by understanding not only what the Entity expresses in terms of Text and Speech but also Face and Gesture. Using this information, the machine can create a textual response and a “simulated” emotion. The second project is Human and Machine Communication that addresses a more extensive version of the same problem.

MPAI Metaverse Model (MPAI-MMM) is a project that has had an evolution similar to that of MPAI-CAV. It was first developed as a single standard, then the Architecture part was started (MMM-ARC). Currently the Technologies (MMM-TEC) V2.0 includes all the results obtained in the 3.5 years since the project was started. The standard enables the development of metaverse instances (M-Instances) that can communicate with other independently designed M-Instances and clients.

Neural Network Watermarking (MPAI-NNW) is an MPAI project developing Technical Reports and Specifications on the application of watermarking and other content management technologies to neural networks. MPAI-NNW V1.0 specifies standard settings to measure the performance of a Watermarked Neural Network. Neural Network Traceability V1.0 extends the methodology to include fingerprinting.

The Object and Scene Description project (MPAI-OSD) is an excellent example of how MPAI standards are developed within one project and then reused by other projects. MPAI-OSD specifies technologies enabling the digital representation of spatial information of Audio and Visual Objects and Scenes for consistent use across MPAI Technical Specifications. Today the definition feels slightly restrictive because the current scope has considerably widened to include a variety of object and scene types beyond audio and video: LiDAR, RADAR, Ultrasound, and even maps.

The Portable Avatar Format (MPAI-OSD) specifies the Portable Avatar (PA) and related data types that enable a receiving party to render a digital human represented by a Portable Avatar as intended by the sending party. Among the data types included in the PA are Text, Speech Model, Avatar – which includes Face and Body Descriptors, and Avatar Model – and Scene Descriptors.

AI Module Profiles (MPAI-PRF) V1.0 enables an instance of AI Module to signal its Attributes – input data, output data, or functionality – and Sub-Attributes that uniquely characterise it. The notion of AIM Profile is being extended to AI Workflows.

Server-based Predictive Multiplayer Gaming (MPAI-SPG) – Mitigation of Data Loss Effects (SPG-MDL) V1.0 provides guidelines on and an example of the design and use of Neural Networks producing reliable and accurate predictions. In case the control data of some players in a multiplayer game based on authoritative server are missing, the predictions can be used to compensate for the absence of control data.

Data Types, Formats and Attributes (MPAI-TFA) V1.4 specifies Qualifiers, data types that facilitate or even enable the operation of an AI Module that receives a data type instance by providing information about Sub-Types (e.g., colour space), Formats (e.g., compression and transport), and Attributes (e.g., metadata) of the data type. Currently, Qualifiers are defined for Automotive, Health, Machine Learning, Media, Metaverse, and Space-Time.