MPAI: where it is, where it is going

Some 50 days after having been announced, MPAI was established as a not-for-profit organisation with the mission to develop data coding standards with an associated mechanism designed to facilitate the creation of licences.

Some 150 days have passed since its establishment. Where is MPAI in its journey to accomplish its missions?

Creating an organisation that would execute the mission in 50 days was an achievement, but the next goal of giving the organisation the means to accomplish its mission was difficult but was successfully achieved.

MPAI has defined five pillars on which the organisation rests.

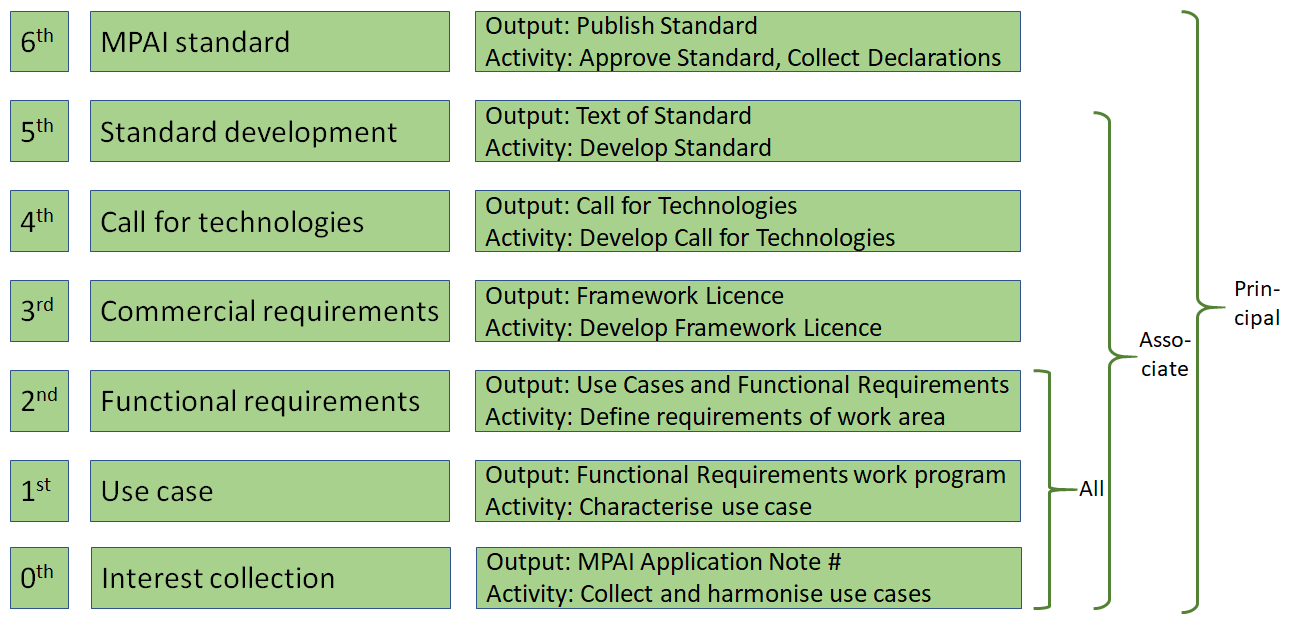

Pillar #1: The standard development process.

MPAI is an open organisation not in words, but in practice.

| Anybody can bring proposals – Interest Collection – and help merge their proposal with others into a Use Case. All can participate in the development of ed Functional Requirements. Once the functional requirements are defined, MPAI Principal Members develop the Commercial Requirements, all MPAI Members develop the Call for Technologies, review the submissions and start the Standard Development. Finally, MPAI Principal Members approve the MPAI standard. |  |

The progression of a proposal from a stage to the next is approved by the General Assembly.

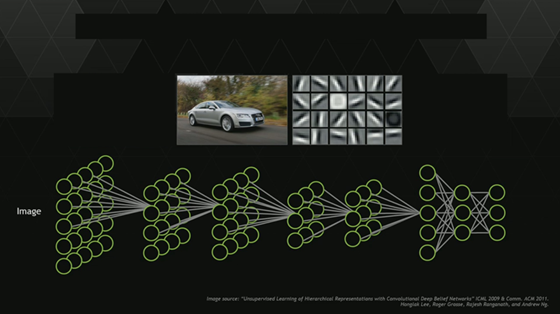

Pillar #2: AI Modules.

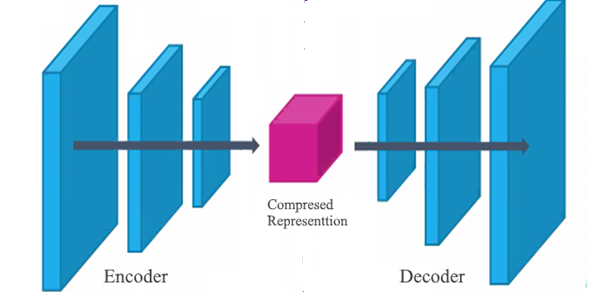

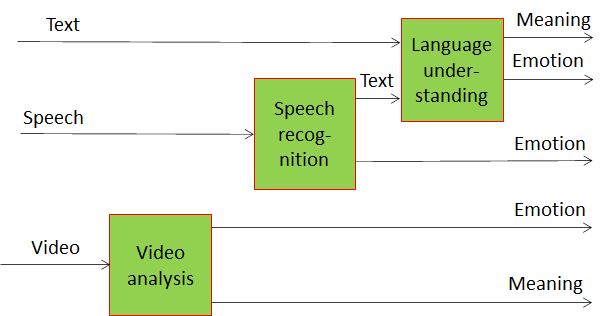

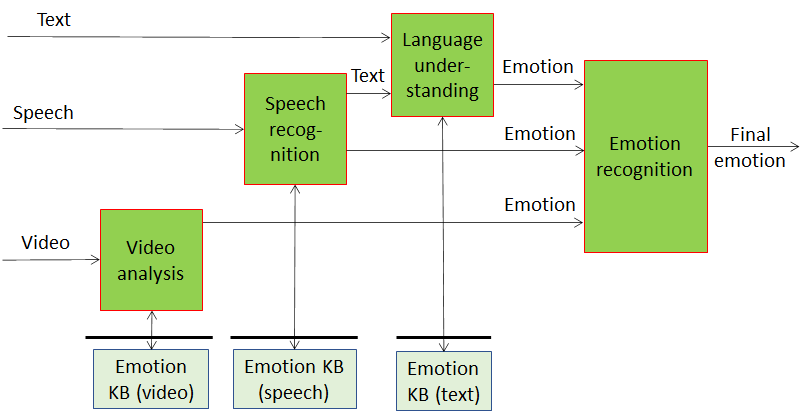

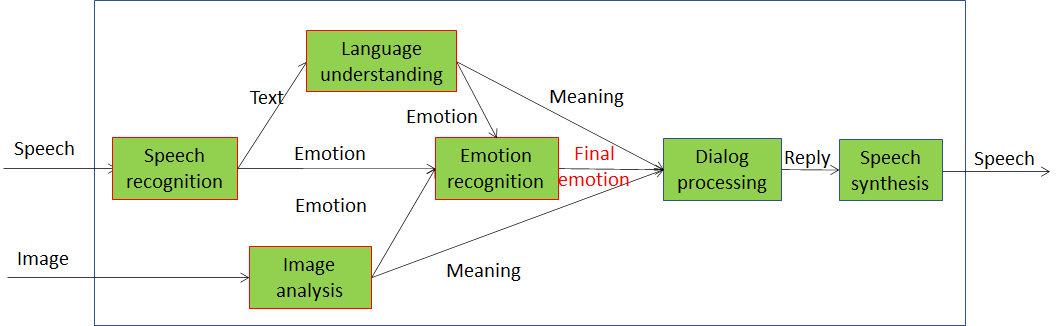

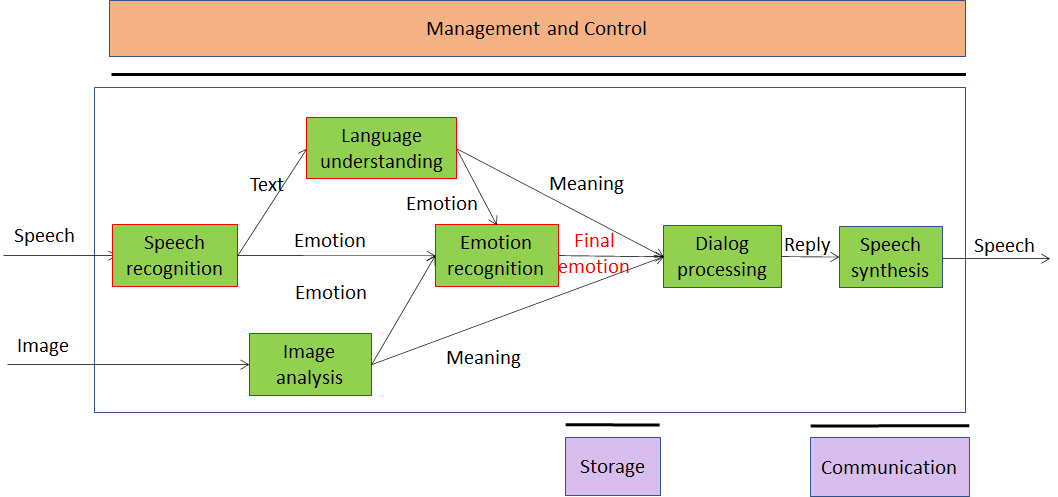

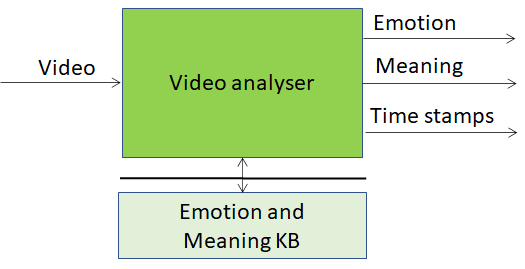

| This pillar is technical in nature, but has far reaching implications. MPAI defines basic units called AI Modules (AIM) that perform a significant task and develops standards for them. The AIM in the figure processes the input video signal (a human face) to provide the emotion expressed by the face, the meaning (question, affirmation etc.) of what the human is saying. |  |

MPAI confines the scope of standardisation to the format of input and output data of an AIM. It is silent on the inside of the AIM (the green box) which can use ML, AI or data processing technologies and can be implemented in hardware or software. In the figure the Emotion and Meaning Knowledge Base is required when the AIM is implemented with legacy technologies.

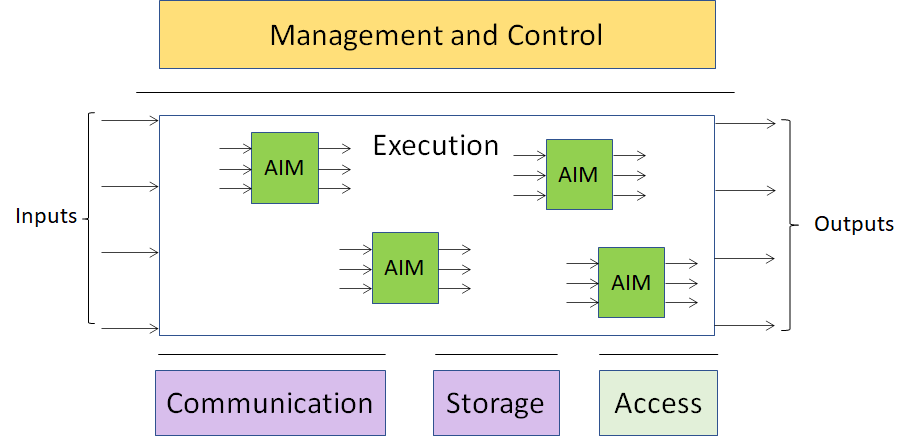

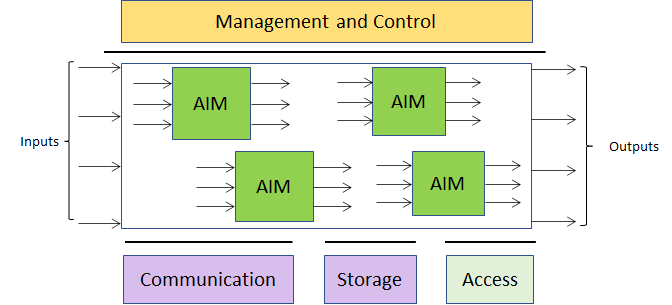

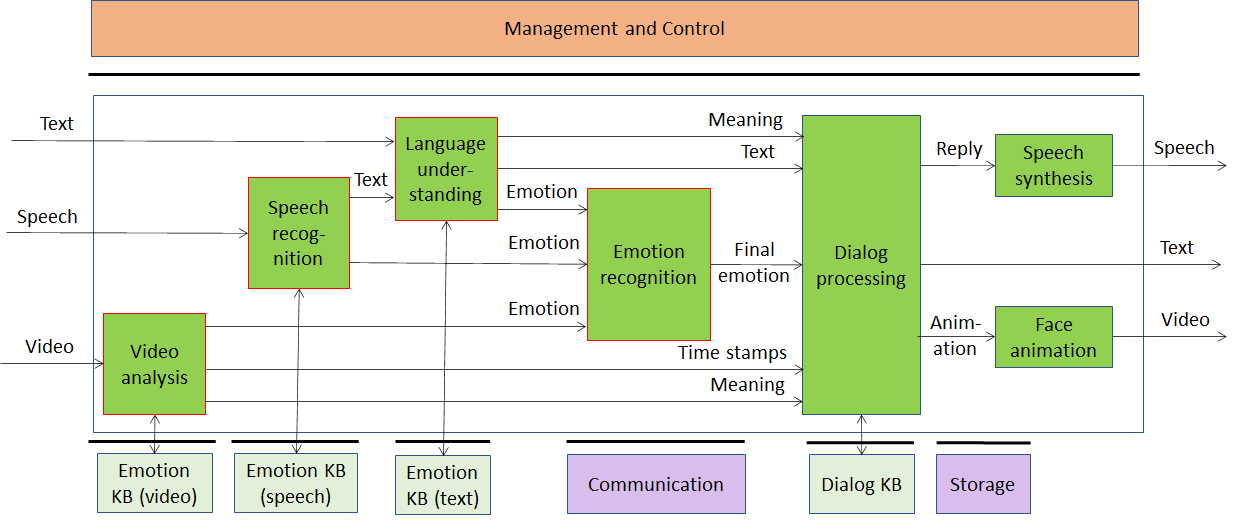

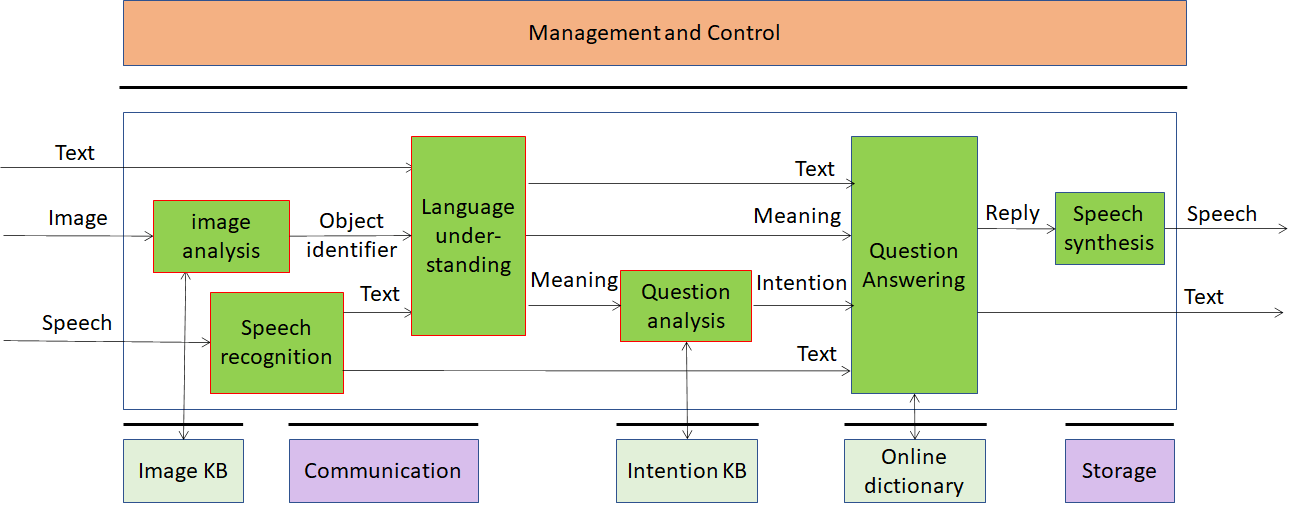

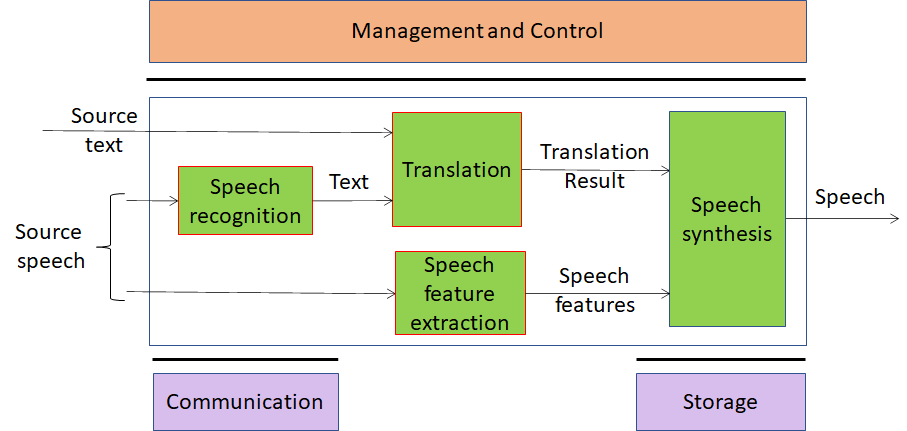

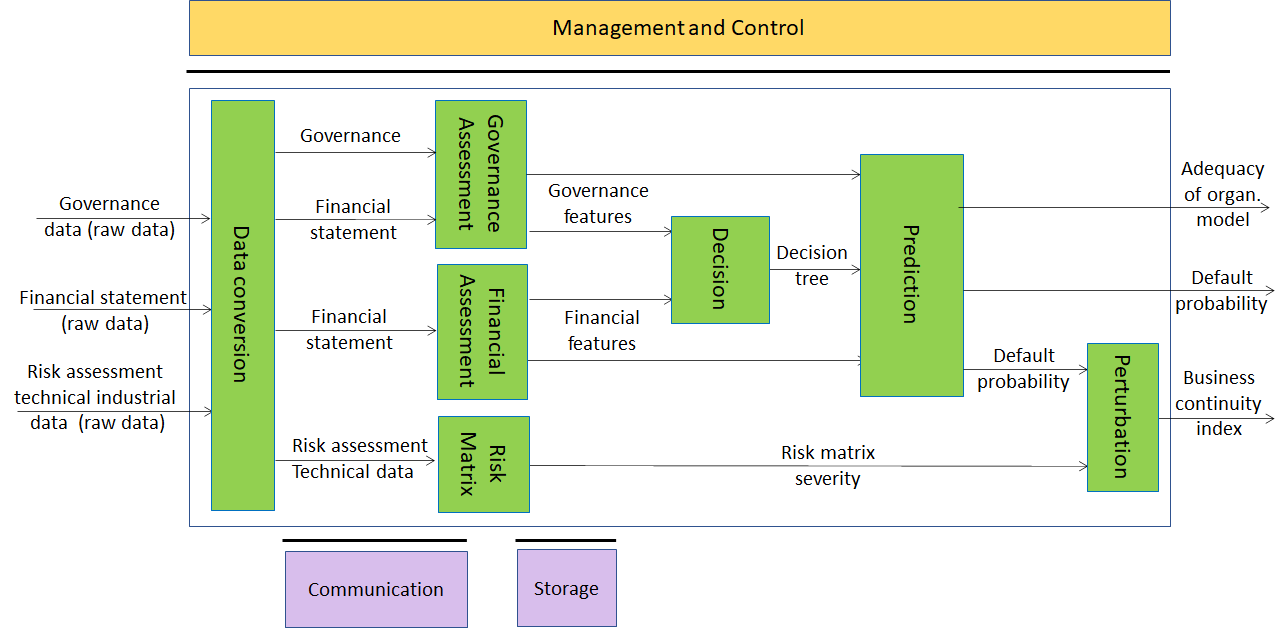

Pillar #3: AI Framework

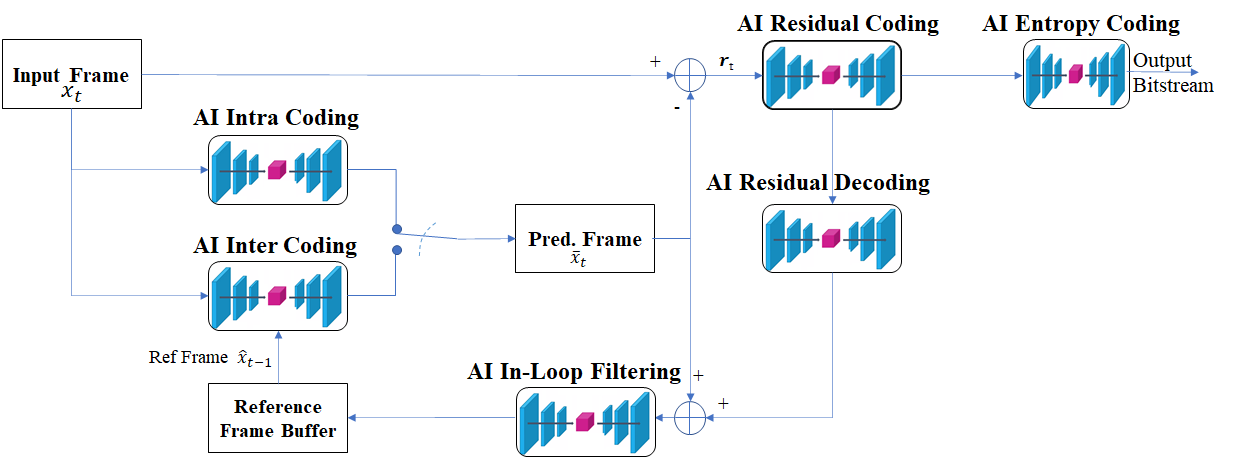

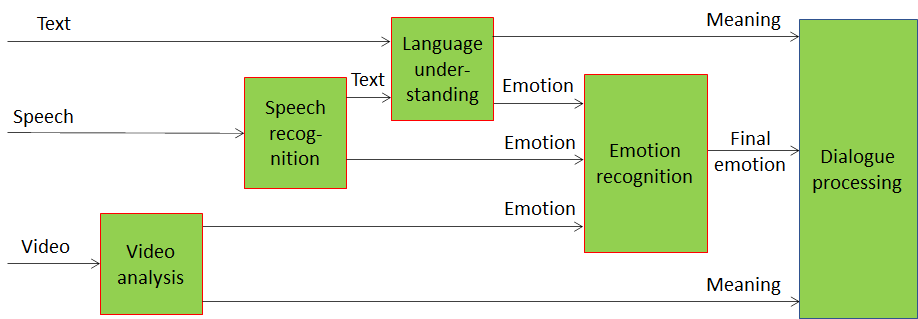

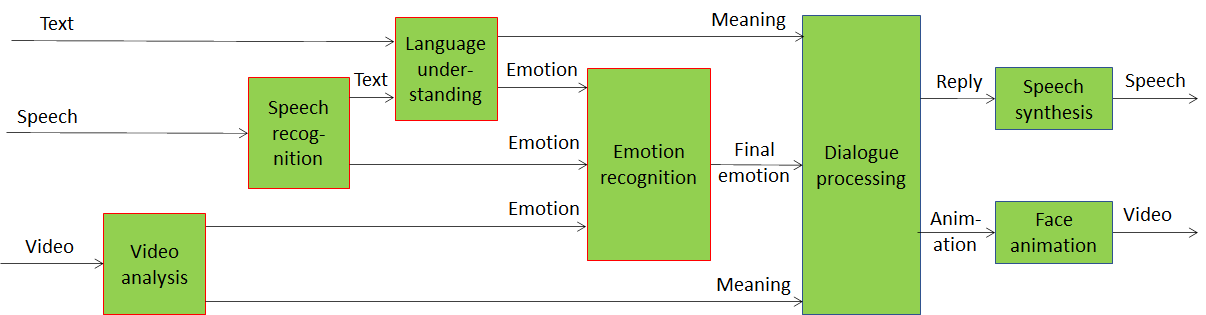

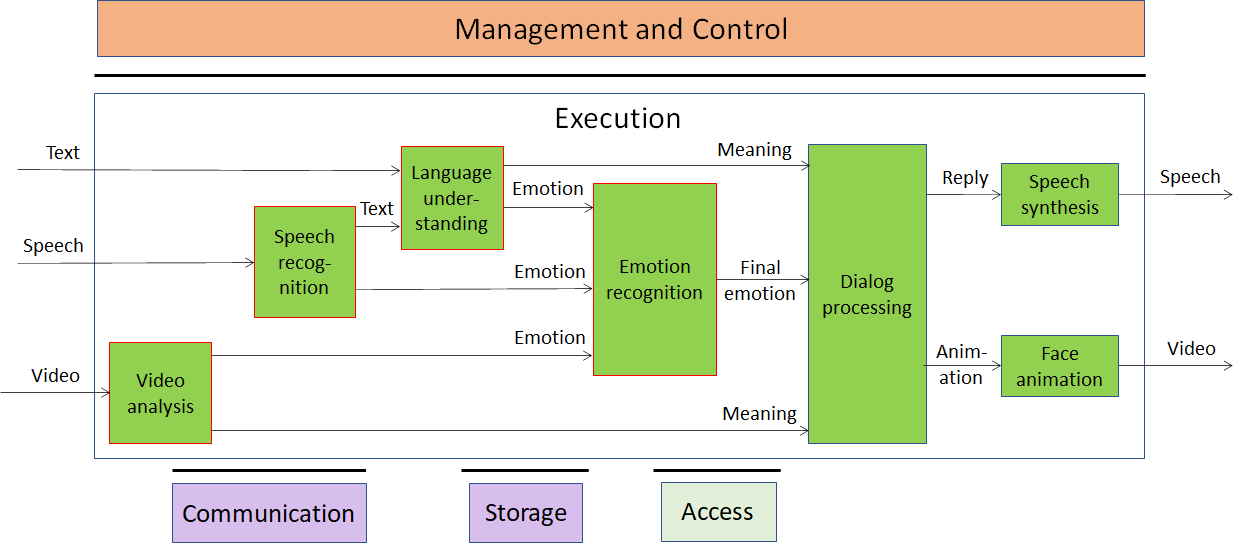

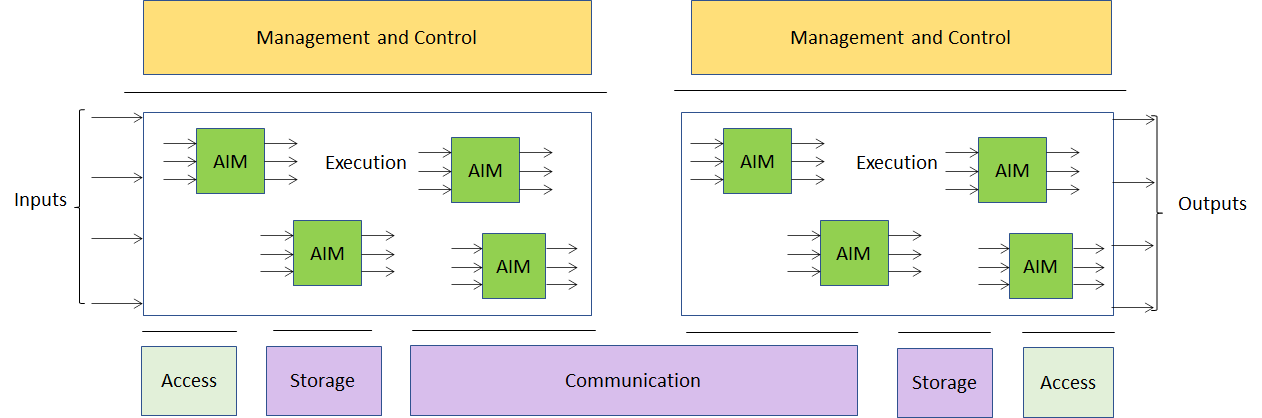

It is clear that, just by itself, AIMs will have limited use. Practical applications are more complex and require more technologies. If each of these technologies are implemented as AIMs, how can they be connected and executed?

| The figure depicts hiw the MPAI AI Framework (AIF) solves the problem. The MPAI AI Framework has the function of managing the life cycle of the individual AIMs, and of creating and executing the workflows. The Communication and Storage functionality allows possibly distributed AIMs to implement different forms of communication. |  |

Pillar #4: Framework Licence

The process of Pillar #1 mentions the development of “Commercial Requirements”. Actually, MPAI Principal Members develop a specific document called Framework Licence, the patent holders’ business model to monetise their patent in a standard without values: dollars, percentage, dates etc. It is developed and adopted by Active Principal Members and is attached to the Call for Technologies. All submissions must contain a statement that the submitter agrees to licence their patents according to the framework licence.

MPAI Members have already developed 4 Framework Licences. Some of the interesting elements of them are:

- The License will be free of charge to the extent it is only used to evaluate or demo solutions or for technical trials.

- The License may be granted free of charge for particular uses if so decided by the licensors.

- A preference will be expressed on the entity that should administer the patent pool of patent holders.

Pillar #5: Conformance

Guarantee of a good performance of an MPAI standard implementation is a necessity for a user. From an implementer’s viewpoint, a measurable performance is a desirable characteristic because users seek assurance about performance before buying or using an implementation.

Testing an MPAI Implementations for conformance means to make available the tools, procedures, data sets etc. specific of an AIMs and of a complete MPAI Implementation. MPAI will not perform tests an MPAI Implementation for conformance, but only provide testing tools that enable a third party to test the conformance of an AIM and of the set of AIMs that make up a Use Case.

The MPAI standards

MPAI has issued

- A call for technologies to enable the development of the AI Framework (MPAI-AIF) standard. Responses we received on the 17th of February and MPAI is busy developing the standard.

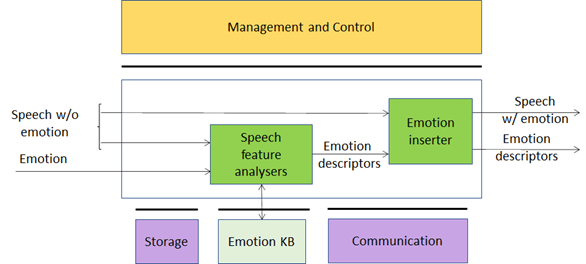

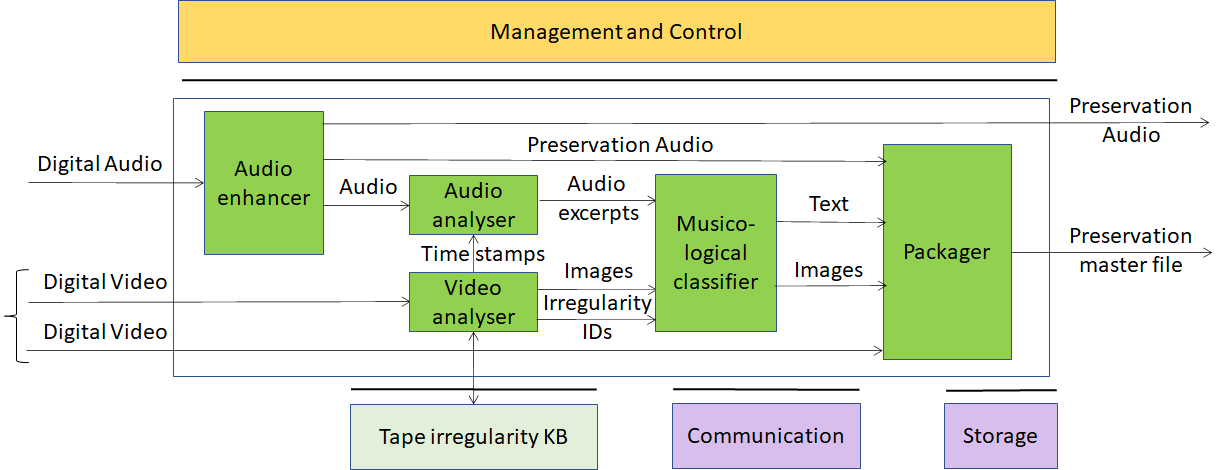

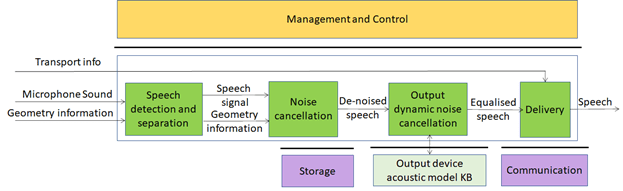

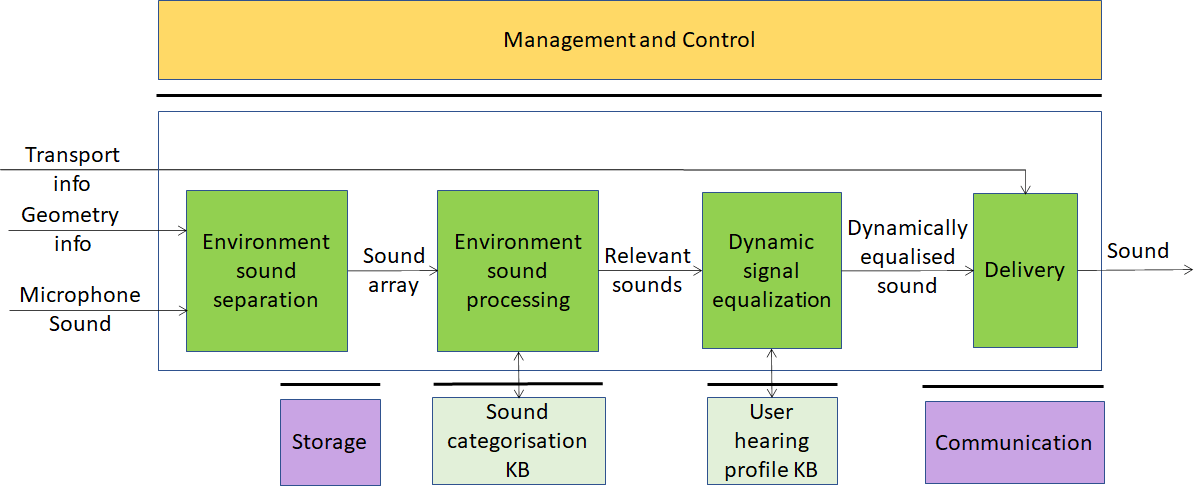

- Two calls for the Context-based Audio Enhancement (MPAI-CAE) and Multimodal Conversation (MPAI-MMC) standards. Responses are due on the 12th of April.

- A call for the Compression and Understanding of Industrial Data (MPAI-CUI) standard. Responses are due on the 10th of May.

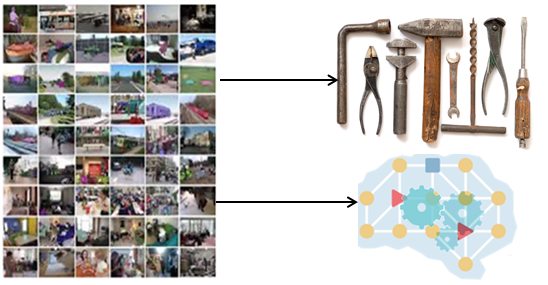

Calls for technologies for a total of 9 Use Cases have been issued. One is being developed. Th Use cases described above are depicted in the figure below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

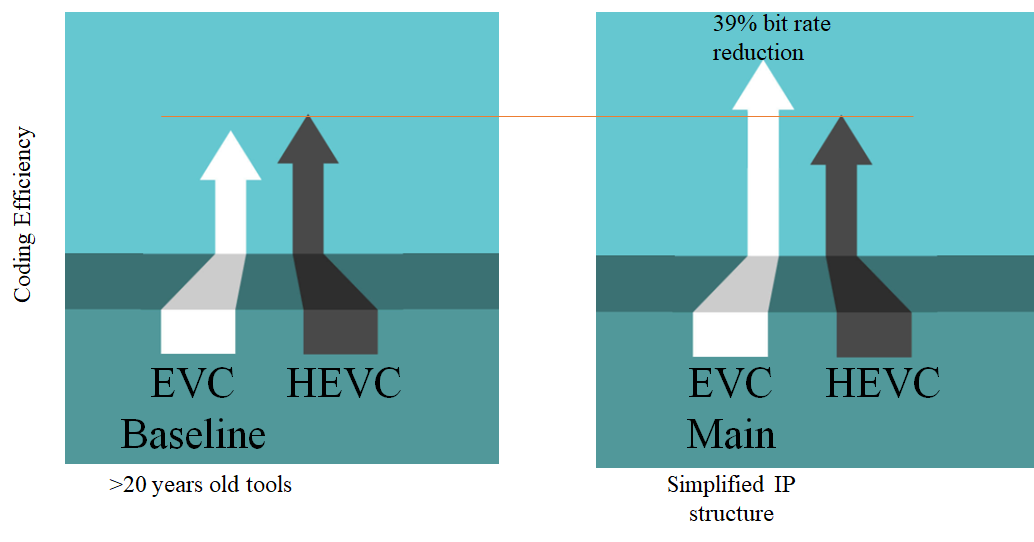

MPAI continues the development of Functional Requirements for the Server-based Multiplayer Gaming (MPAI-SPG) standard, the Integrated Genome/Sensor Analysis (MPAI-GSA) standard and the AI-based Enhanced Video Coding (MPAI-EVC).

In the next months will be busy producing its first standards. The first one – MPAI-AIF – is planned to be released on the 19th of July.